Noh Plays

Noh Plays

As many as 2,000 noh plays have been created over the seven-hundred-year history of the art form. They depict a wide range of sentiments, resentments, and conceits, featuring themes such as the belief in gods, beasts, demons, and the transformation of humans into fiends, as well as the misery of war, maidenly love, female jealousy, and the love between parents and children.

Okina: The Source of Noh

Okina: The Source of Noh

Every locale has had its own myths since ancient times:

“The deity descended from the heavens …”

“The deity visited from far off over the sea …”

And “The gods bring blessings to mankind …”

The ritual noh of Okina embodies such beliefs by giving them visible form on stage. The prayers expressed in the performance of Okina are the origins of noh.

It is said that “Okina is noh, yet is not noh.” It is totally different from other noh plays because it has no story. The performance does not aim at amusement.

In a solemn dance of prayer to Heaven, Earth, and Man, the whiteOkina invokes blessings.

In a lively dance for a good harvest, the black Okina mimics the breaking up of the soil and the sowing of seeds.

Only in the performance of Okina is the mask donned on stage. Only in Okina are there three kotsuzumi (small hand drum) players. Okina always precedes other plays in a day’s program of performances.

Mugen Noh, a Special

Mugen Noh, a Special

Dramaturgy Unique to Noh

Noh includes plays called mugen noh (phantasmal or dream noh) which are built on dramaturgical constructs not found in other forms of theatre.

Theatrical plays enact stories that progress from a beginning to an end, the events typically unfolding on stage in chronological order. Noh plays that follow this structure are known as genzai noh, or “noh in the present time.”

Unlike genzai noh, in mugen noh the flow of time plays out freely, following the recollections and the vacillating thoughts of the main character. Time reverses course, reaches backward, moves forward, and returns to the present.

This temporal flexibility is necessary because the play reflects the reminiscence of the protagonist’s past and the turmoil of their ongoing feelings.

The spirits of those who harbored deep resentments while alive, and remain unreconciled even in death, return to this world. Speaking through the intervention of religious practitioners, they relate the stories of their past and seek help in attaining Buddhahood.

Types of Noh Play and the Five Category System

Types of Noh Play and the Five Category System

In addition to differentiating between types of noh based on compositional structure (mugen noh and genzai noh), the noh repertory is also categorized according to the characteristics of its key figures. Noh plays have been grouped into five categories according to their style and type of main character. This is called the Five Categories (Gobandate) system.

During the Edo period (1603–1868), a day’s program included four to six plays. In order to avoid similar plays following in succession, one play from each category was chosen, and a kyogen comedy was inserted between each successive pair.

Firelight Noh, a Special

Firelight Noh, a Special

Performance Space

Noh performed outdoors by

firelight presents a fantastic,

vision-like spectacle.

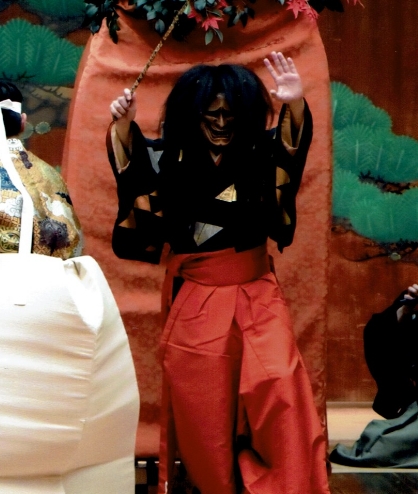

Firelight noh (takigi noh) refers to noh performed on a temporary stage surrounded by burning flares.

A phantasmal atmosphere envelops these torchlit performances, creating a deeply moving experience. Traditionally many takigi noh have taken place in temples, shrines, and on castle grounds.

Even today, performances with a seasonal dimension are held in various parts of Japan, set against a backdrop of natural beauty: cherry blossoms in spring and the full moon in autumn.

- Takigi Noh at Osaka Castle

Noh Playwrights

Noh Playwrights

Most of the noh in today’s repertory were created during the Muromachi period (1336–1572). The plays based on famous classical stories such as the Tale of Genji, the Tale of the Heike, waka poems, and renga linked verse, are thought to have been written by highly erudite people.

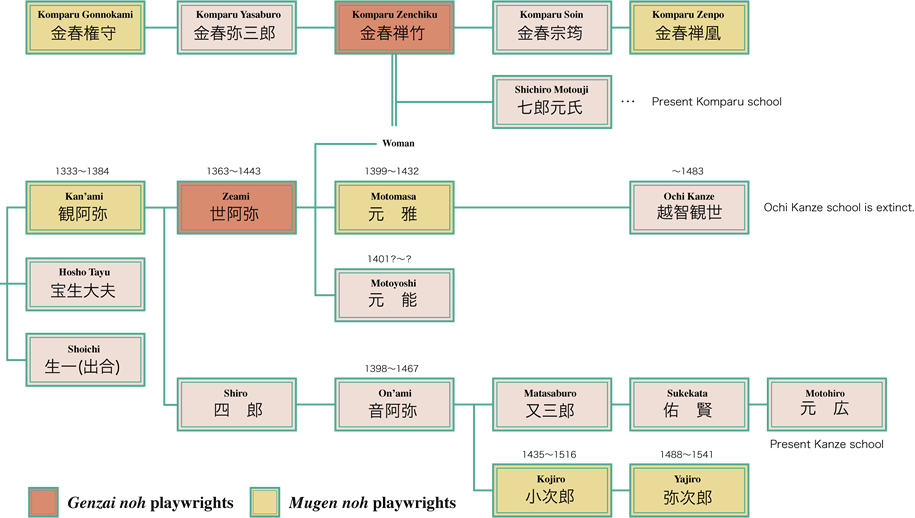

The majority of the plays were written, composed, performed, and passed down by the actors themselves. After the death of Kan’ami and Zeami, the father and son who developed noh into its mature form, important noh playwrights included Zeami’s successors and members of the Komparu family.In addition, some highly esteemed noh plays written by amateur performers or people with no theatrical background at all have been incorporated into the repertory. Since the playwrights did not sign their names on the scripts, it is often difficult to determine who was the author of any given play.

- The Key Muromachi-period Noh Playwrights

-